Architecture’s forgotten figures

By Despina Stratigakos

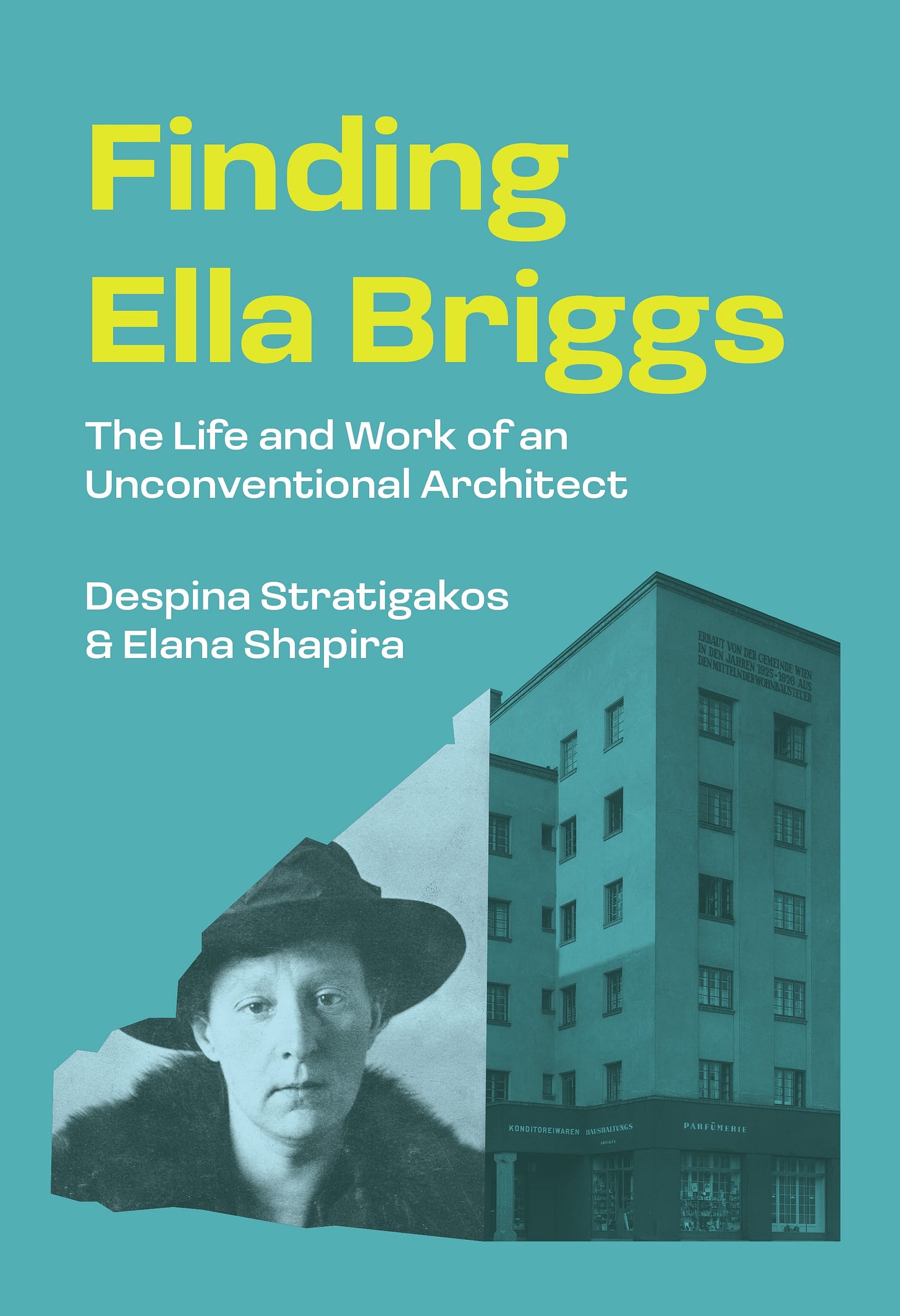

How do we lose architects to time? Especially ones that leave behind buildings so massive and visible that it is hard to imagine their names will ever be forgotten? Like any other subject, the history of modernist architecture has its favored heroes and plotlines, but also important figures who drop out of sight despite their contemporary successes. Ella Briggs is one of them.

Born into a Jewish family in Austria in 1880, Briggs was one of those rare people whose life trajectories put them smack in the middle of major historical developments. Having studied with the Secessionists in Vienna, who revolutionized the world of modern art and design at the turn of the twentieth century, Briggs moved to Gilded Age New York and quickly rose to prominence as an interior designer bringing original ideas to America.

When a few years later she returned Vienna, she opened her own design studio. During the First World War, she fought for admission to architecture studies, still then mostly closed to women, who were thought to lack the cognitive abilities and physical strength needed for the profession. In the 1920s, working as an architect in both Europe and the United States, Briggs was a conduit for emerging trends in modern living and spaces as she travelled back and forth across the Atlantic.

Very much her own person, Briggs was unafraid to cast a critical eye on how people lived or how architects built. She wrote for magazines and journals read by a popular audience and by professionals, raising her profile. In Austria, she was one of only two women architects (the other being Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky) who participated in the projects of Red Vienna, a vast social housing program intended to uplift the working classes. Her Pestalozzi-Hof, a large apartment complex, and Ledigenheim, Vienna’s first municipal residence for single people, won critical acclaim.

In the late 1920s, Briggs moved to Berlin, then a red-hot center of modernist building and debates. There she entered the fray through her architectural projects, exhibition designs, and writings for newspapers and magazines. Contemporaries referred to Briggs as “a famous lady architect,” a perception she encouraged. She worked hard, played the publicity game, and seemed poised to enter the history books.

Then Adolf Hitler came to power. The outspoken Briggs was targeted by an SS-Mann for her “insolence” to the regime. She fled Germany for England, one of many refugee architects who lost everything and had to start over again. Even so, she forged ahead, earning new qualifications and sending out CVs in her sixties. She obtained one last major commission, designing Stowlawn Estate in Bilston according to concepts borrowed from Red Vienna housing projects. Even after she gave up her architecture practice, she remained an avid contributor to Homes and Gardens, offering housing advice to British readers reemerging from years of war deprivation. Briggs died in London in 1977 at the age of 97, without an obituary to mark the passing of this once “famous lady architect.”

After her death, Briggs’s name lingered in the margins. Yet there were no major writings about her, largely because she did not fit the frameworks of mainstream modernist histories. To begin, she was a woman, and women in architecture were overlooked by historians for decades, even when their names were recognized and respected in their own time. She also led a peripatetic lifestyle, travelling and working in many different countries. This is a pattern we see with women in architecture who often had to relocate to find work. For Briggs, though, there was also joy in encountering new ideas, which she embraced and adapted as needed. A historian’s travel budget rarely stretches far enough to cover such a broad geographical swath of research, never mind the linguistic and cultural knowledge also needed to understand these differing artistic, cultural, and political contexts.

An even greater hurdle Briggs posed to historians was her defiance of strict ideas about modernist style. Briggs shared modernist concerns about hygienic homes with plenty of sunlight and air. But she did not care if a building had a flat or pitched roof, and she admonished architects who designed a house according to aesthetics over function. For her, a modernist house eased living, especially for the tired housewife. Briggs centered the user in her design process, believing an architect should adapt to client desires and needs.

Despite historians’ recent interest in user-focused design, which is bringing new modernist projects and practitioners to the fore, Briggs remained exceptionally difficult to write about. And that is because we cling to the idea of the lone scholar, laboring away at a desk until a book emerges fully formed from her head. Some histories—and Briggs’s is one of them—cannot be written in this way. It took a team of researchers—historians, archivists, curators, and architects—working together across four countries to bring Briggs’s story to life. Yet our universities, grant-making agencies, and even most publishers are not set up to accommodate this way of working in the humanities.

Finding Briggs took not only discarding outdated ideas about modernism, but also questioning the entire apparatus of how we write. In pursuing this history, we became the Ella Briggs Detective Brigade, as we half-jokingly called ourselves. It was exhilarating, sometimes challenging work, and in the end, we could barely believe what we had found. Which begs the question: how many more “lost” stories are out there, waiting for a brigade of detective-historians to uncover them?

About the Author

Despina Stratigakos is SUNY Distinguished Professor in the Department of Architecture at the University at Buffalo, State University of New York. Her books include Where Are the Women Architects? (Princeton) and A Women’s Berlin.

https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691263953/finding-ella-briggs

Very interesting. I hadn't heard of her.